Our Strategic Petroleum Reserve Becomes a Political Plaything

After buying votes with oil, the Biden administration has placed the country in jeopardy.

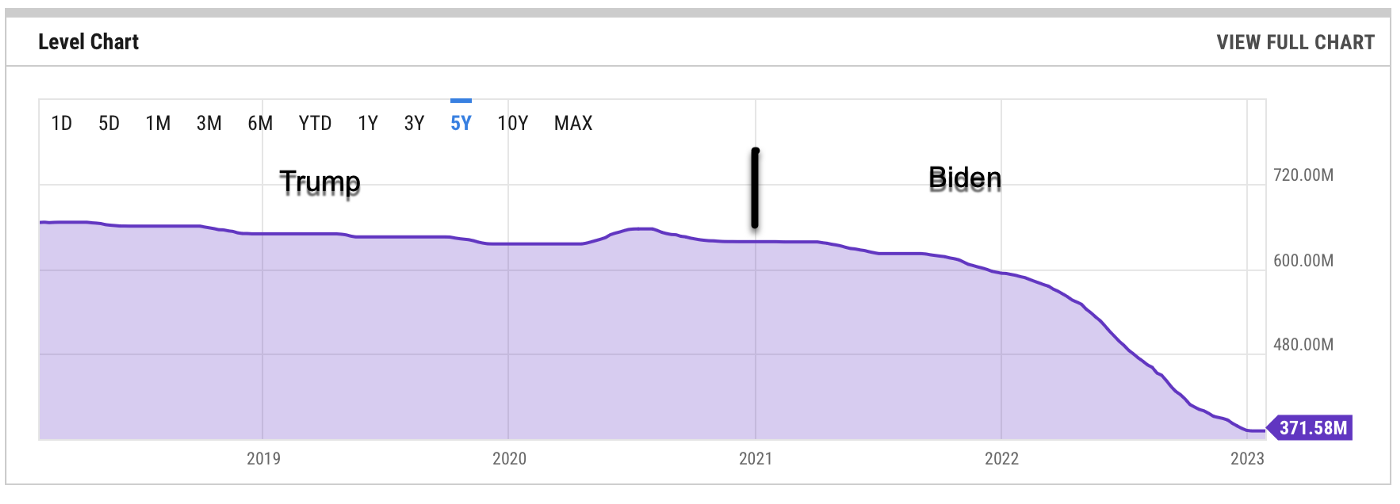

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) is supposed to function as America’s ace in the hole in the event of a major structural or geopolitical disruption of the nation’s oil supply. In early 2021, the Biden administration began to radically withdraw oil, 180 million barrels, from the reserve for purely political reasons — to increase supply in the hope it would lower inflation-driven energy prices in time for the crucial mid-term Congressional elections in November 2022. The unprecedented drawdown worked out to 1 million barrels per day for six months (Figure 1). The ploy worked…to a degree…but Americans are seeing gasoline prices approaching five dollars a gallon again in February 2023. At the same time, the SPR has been depleted to the point where it is no longer a viable option for reducing gasoline prices. The levels in the reserve are simply too low to risk further drawdowns. The U.S. could find itself between a rock and a hard place in the event of a major supply disruption.

The Petroleum Reserve is Dangerously Low

The U.S. began filling the reserve in 1977 and it reached its maximum level of 726 million barrels in December 2009. Thereafter, the reserves declined slowly in response to mandatory sales, test sales, exchanges, and other factors.

Between October and December 2021 (FY 2022) a mandatory sale of 20 million barrels was initiated (Figure 2). Another mandatory sale of 18 million barrels took place between January and March of 2022. During the period December 2021 through April 2022, a 32-million-barrel competitive exchange took place, with the oil plus the additional “premium” barrels to be repaid by the end of FY2024. All of this is a relatively normal course of business for the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.[i]

By early 2021, several massive stimulus packages passed by Congress had begun to fuel inflation, which reached almost 13 percent by Spring. With energy prices skyrocketing and the mid-term elections looming in November 2022 and facing the possibility of a Republican “red wave,” President Biden began releasing oil from the SPR: 30 million barrels between April and May 2022, another 70 million barrels between May and July, and 90 million barrels between August and the end of October at the height of the mid-term campaigns. These drastic drawdowns reduced the crude oil inventory in the SPR to 361 million barrels by the end of December 2022. As of the end of January 2023, the inventory had risen slightly to 371.6 million barrels.

By any measure, these stocks are now at a dangerously low level. Facing criticism for the politically motivated drawdowns, the Biden administration announced a 3-million-barrel purchase that would begin refilling the SPR when the price reached $70 per barrel, to take place in February. As of this writing (Feb 6), the price of West Texas Intermediate crude is $74.49 a barrel; Brent crude is $80.99 per barrel. Every common grade of crude oil is priced above the administration’s offer price.

The first offer for purchase by the federal government was rejected by the Department of Energy as too expensive; sellers refused to sell crude oil at a price the government was willing to pay. Refilling the SPR will not be as easy as expected. Keep in mind, also, that the average price of all the oil in the SPR was $29 per barrel as averaged over the life of the reserve. We bought cheap and now we may be forced to buy high.[ii]

To prevent the White House from using the Strategic Petroleum Reserve as a political plaything, House Republicans in January introduced the Strategic Production Response Act to prevent the president from releasing any oil from the reserve except in the case of a carefully defined severe energy disruption, unless the president at the same time opens more federal lands to oil and gas leasing. Predictably, Democrats have blasted the proposed legislation as “putting wealthy special interests ahead of middle-class families.”[iii]

This, of course, is not the first time politics has stymied maintaining our strategic oil stockpile. In early March 2020, oil prices had plunged to record lows due to lowered demand caused by the pandemic and President Trump proposed purchasing up to 75 million barrels of oil for the SPR at a cost of around $2.5 billion, enough to effectively top off the reserve.[iv]

Senate Democrats were having none of it. Instead of taking advantage of record-low oil prices to ensure our energy security, the Democrats stripped the money from the stimulus bill in late March, calling it a “bailout for the oil industry.”[v]

What is the Strategic Petroleum Reserve?

The SPR was created by the Energy Policy and Conservation Act, signed by President Ford in 1975, in response to the Arab oil embargo of 1973–1974. The idea of an oil reserve had been considered as early as 1944, but the Arab embargo brought America’s vulnerability to energy disruptions to the fore and was the final impetus to force the government to act.

At the same time, the U.S. was one of the founding members of the International Energy Agency (IEA), formed to create a collective response to energy supplies and build reserves to guard against future disruptions. With 31 member countries (and four awaiting membership), the IEA’s mandate is cooperation on “security of supply, long-term policy, information transparency, energy efficiency, sustainability, research and development, technology collaboration, and international energy relations.”(vi) The agency’s emergency response mechanism has been activated four times since its inception.

One of the IEA’s mandates is for member countries to hold in reserve strategic stocks equal to 90 days’ supply, based on the previous year’s net imports. Countries that are net exporters are not required to meet the reserve requirement. The U.S. was a net exporter in 2021 and was thus exempt from the 90-day reserve.

The Structure of the SPR

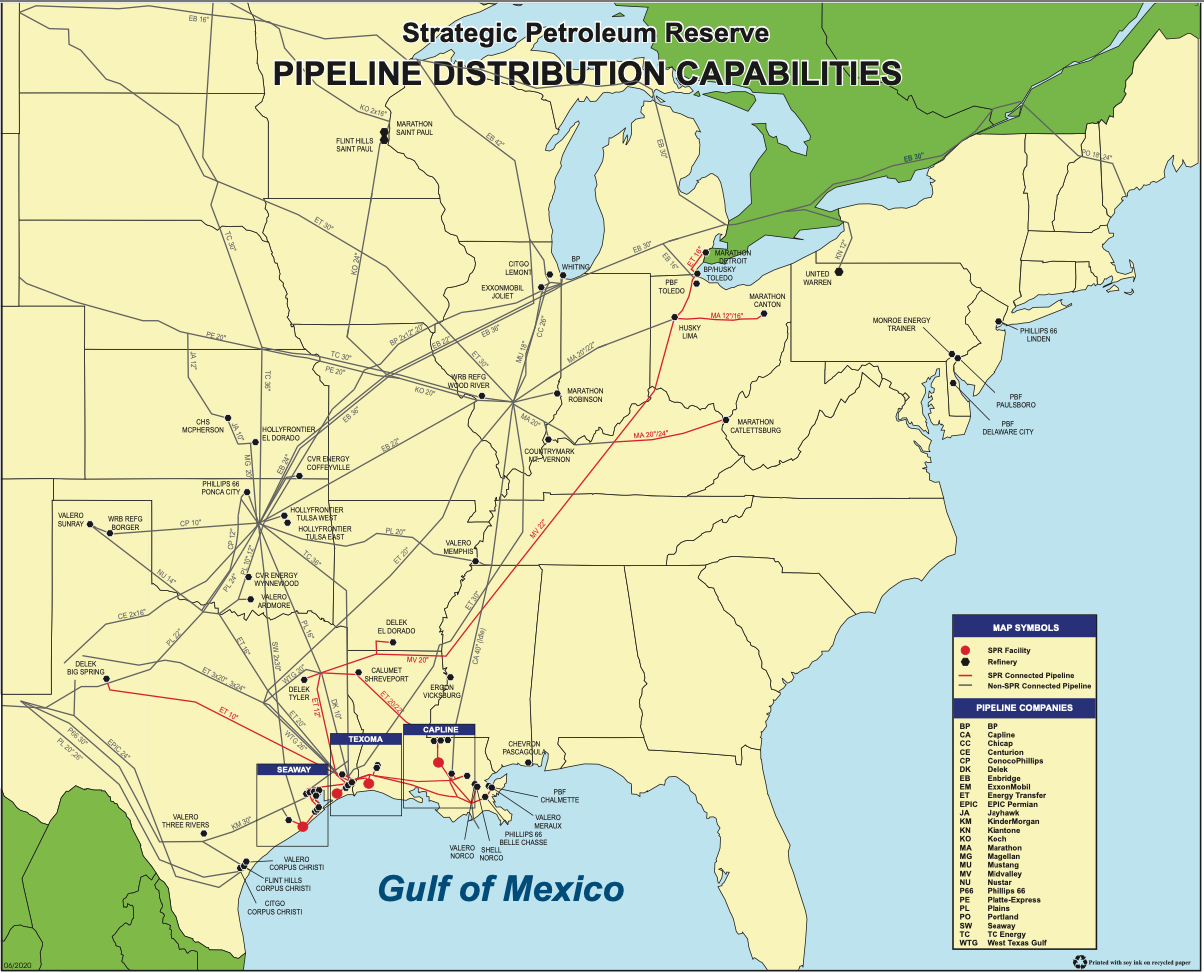

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve consists of four sites located on the Gulf coast, two in Texas and two in Louisiana, with a total storage capacity of 713.5 million barrels of oil.[vii] The sites consist of a total of 60 caverns within extensive salt domes underground. Plans to expand the SPR’s capacity to one billion barrels were approved but later canceled by the Obama administration in 2011. Although the SPR is authorized to store crude and refined products, it has only historically held crude oil. This is because refined products, such as gasoline, tend to deteriorate rather quickly and are thus unsuited for long-term storage.

The storage caverns are carved within the salt domes by drilling wells through the caprock into the salt and then pumping large amounts of fresh water into the salt to dissolve it. The resulting brine is then pumped into holding tanks or, more commonly, piped several miles offshore and released into the Gulf of Mexico. This technique can create caverns of precise size and uniformity. Each cavern has an average diameter of 200 feet and a height of 2,550 feet, large enough to hold Chicago’s Willis Tower (the former Sears Tower) with room to spare.

Salt caverns have many advantages over above-ground storage. Using above-ground tanks can cost $15–18 per barrel, compared to $3.50 per barrel for underground storage in salt caverns. Salt, if relatively pure, is impervious to liquid or gas and inert to petroleum. Beneath the weight of the overlying and surrounding rock, salt has a compression strength equal to that of concrete. Due to the caverns’ depth, geological pressures keep cracks from forming and those that do are sealed by the salt’s plasticity. Finally, the height of the cavern ensures a temperature difference between the top and bottom, which causes the oil to circulate within the cavern and maintain consistency throughout.

The salt caverns do have a vulnerability, though. To retrieve the oil from the caverns, called a drawdown, water is pumped into the bottom, forcing the oil up and out. Each drawdown leaches an amount of salt from the cavern. Sandia Laboratories, in a 2022 annual report[viii], estimated a total drawdown of an individual cavern, defined as withdrawing 90% of the oil with raw water, would leach an assumed 15% of the salt from the cavern. Full drawdowns are rarely performed, however, which means the leaching from partial drawdowns is confined almost entirely to the bottom portion of the cavern. Axisymetrical caverns are better able to withstand repeated withdrawals than those with irregular shapes.

Distribution and Sales

As mentioned, the SPR consists of four storage sites (Table 1).

Each of the storage sites has access to a marine terminal and pipelines, allowing distribution to half of the refineries in the country as well as facilitating the refilling of the reserve. The maximum rate of withdrawal is 4.4 MMB/D and it takes 13 days for the oil to reach the open market. The effect of a withdrawal announcement is often quickly felt in the markets as the oil’s arrival is anticipated.

Historical Oil Releases

There are several reasons why a sale of crude oil from the SPR might take place. First and foremost, releases have been ordered to meet emergencies caused by supply disruptions. Presidents have ordered releases on four occasions deemed emergencies: 1991 during Operation Desert Storm; 2005 after Hurricane Katrina; an IEA-coordinated release in 2011 due to oil disruptions in Libya; and President Biden’s political “emergency” in 2021–2022. A full or limited drawdown can only be authorized by a sitting president. The Department of Energy can conduct test sales or exchanges.

As mentioned, test sales are occasionally conducted to test equipment, determine that drawdown rates meet specifications, and evaluate sale procedures. Test sales are limited to 5 MMB (million barrels). Test sales were held in 1985, in 1990 during Desert Shield, and in 2014.

The Secretary of Energy is authorized to release oil on loan or exchange with refineries to mitigate short-term disruptions such as a blocked ship channel. These sales are generally Royalty-In-Kind, where the borrower pays back the oil to the SPR plus a smaller additional amount, like interest. Twelve exchanges were initiated between 1996 and 2017, all due to hurricanes or shipping channel blockages. These drawdowns are typically no more than 30 million barrels.

Sales have also been authorized to generate revenue for SPR site maintenance and upgrades, called Life Extension Programs. LEP 1 was initiated in 1993 for $324 million to ensure drawdown capability across all four sites. In 2015 LEP 2 began upgrading equipment at all four sites. Modernization sales took place in 2017, 2018, and 2019.

Congress can also mandate sales to reduce the deficit or raise funds for programs, as was done in 1996–1997. All told, the SPR has released over 230 million barrels of crude oil through 2019 and another 180 million barrels since 2021.

Our immediate future…precarious

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve has now been drawn down to its lowest level since September 1983, placing the country on a slippery footing in the event of a major supply disruption. At the maximum withdrawal rate of 4.4 million barrels per day, it would take 85 days for a full withdrawal. From the president’s order to release oil to its entry into the market takes about 13 days. Released at a rate of 1 million barrels per day, the reserve would take just over a year to drain. Americans consumed almost 20 million barrels per day of petroleum products in 2021, so 1 million barrels per day doesn’t go very far.

Refilling the reserve currently is problematic, with the price of crude oil hovering around $75 to $80 per barrel, well above the administration’s target price of $68 to $72 a barrel. Oil purchases in the immediate future are apt to be expensive, even though the Energy Information Administration projects the price of crude oil to decrease during 2023 and 2024 and domestic production to increase. As noted, the February 2023 crude oil purchase was canceled by the government when bid prices came in at a higher-than-expected level.

More disturbing, the Strategic Petroleum Reserve is subject to manipulation for political purposes, as was done in 2021–2022. This contradicts the words strategic and reserve in the program’s name. While legislation has been introduced to force the use of the reserve to conform more to its intended emergency purpose it is unlikely to survive the current Congress.

Americans should keep a wary eye on future drawdowns of our crude oil insurance policy and demand that it be used for its intended purpose and not as a plaything to be exploited for political purposes. Our future security depends on it.

[i] Brown, Phillip. “Strategic Petroleum Reserve Oil Releases: October 2021 Through October 2022.” (2022): https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11916.

[ii] Smith, Yves. “Washington Has Trouble Filling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve After 220 Million Barrel Draw.” (2023): https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2023/01/washington-has-trouble-refilling-the-strategic-petroleum-reserve-after-220-million-barrel-draw.html.

[iii] Nazaryan, Alexander. “White House Blasts ‘Backwards’ Republican Proposal on Strategic Petroleum Reserve.” (2023): https://news.yahoo.com/white-house-blasts-backwards-republican-proposal-on-strategic-petroleum-reserve-220700865.html.

[iv] Schroeder, Robert. “Trump Seeks to Add 75 Million Barrels of Oil to Strategic Petroleum Reserve Amid Historic Price Crash.” (2020): https://www.marketwatch.com/story/trump-seeks-to-add-75-million-barrels-of-oil-to-strategic-petroleum-reserve-amid-historic-price-crash-2020-04-20.

[v] Hulac, Benjamin J. “Oil Purchase to Fill Strategic Reserve Dropped from Stimulus.” (2020): https://rollcall.com/2020/03/25/oil-purchase-to-fill-strategic-reserve-dropped-from-stimulus/.

[vi] “History — from Oil Security to Steering the World Toward Secure and Sustainable Energy Transitions.” (2022): https://www.iea.org/about/history.

[vii] Greenley, Heather. “The Strategic Petroleum Reserve: Background, Authorities, and Considerations.” R46355 (2020):

[viii] Hart, David, Zeitler, Todd, and Sobolik, Steven. “2022 Annual Report of Available Drawdowns for Each Oil Storage Cavern in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.” (2022): https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1870557.